Kusanthula Vipendero

Kusanthula vipendero ni chisambiro cha ndondomeko izo zikugwiliskika kusanga mazgoro agho ghakusendelera waka ku zgoro lenecho (mwakupambana na [[symbolic computation|kuseŵezga manambara mwakuchiti tisange manambara ghenecho nkhanira-nkhanira) pa masuzgo gha kusanthula kwa samuzi (Kupambana na samuzu ghapadera). Ntchigaŵa cha masambiro gha manambara agho ghakovwira kusanga nthowa zakumazgira masuzgo m'malo mwa kusanga mazgoro ghakwenelera ghankhanira nkhanira. Kusanthula wakugwiliskira nchito vinthu vyose vya sayansi, Ndipo mu vyaka vya m'ma 2000, likugwiliskirika nchito mu umoyo, sayansi, munkhwala, bizinesi na luso wuwo. Kukura kwa nkhongono ya kompyuta hŴakaŵa na mwaŵi wakugwiliskira ntchito nthowa zakusuzga chomene pa Kusanthula, kupeleka vyandulo vya masamu mu sayansi. Viyelezgero vinyake vya 'kusandula' ni ivi: viyanjano vyapadera vya waka nga umo viliri mu makina gha vyakucanya (kumanya umo mapulaneti, nyenyezi, na vipingausiku vikwendera), algebra ya mulingo ya vipendero mu kusanda mauthenga,[2][3][4] na chiyanjano cha upambano cha stokastic na maunyolo gha Markov pakuyelezgera maselo ghamoyo mu vyamankhwala na kusanda-umoyo.

Pambere makompyuta ghandaŵeko, [kusanthula]] Kanandi ŵakugwiliskira ntchito nthowa zakuŵikapo pakati na mawoko, Kufumiska mauthenga kufuma mu mathebulu ghakurughakuru. Kwambira m'ma 1900, makompyuta ghakuchita mawerengero gha mauteŵeti agho ghakukhumbikwa, kweni vigaŵa vinandi vya malemba agha vikulutilira kugwiliskirika nchito mu mapulogiramu gha mapulogiramu gha pa kompyuta.[5]

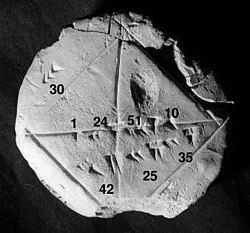

Fundo iyi yikamba kulembeka mu mabuku ghakwambilira gha masamu. Libwe la dongo from the Yale Babylonian Collection (YBC 7289), gives a sexagesimal numerical approximation of the square root of 2, the length of the diagonal in a unit square.

Numerical analysis continues this long tradition: rather than giving exact symbolic answers translated into digits and applicable only to real-world measurements, approximate solutions within specified error bounds are used.

General introduction

[lemba | kulemba source]The overall goal of the field of numerical analysis is the design and analysis of techniques to give approximate but accurate solutions to hard problems, the variety of which is suggested by the following:

- Advanced numerical methods are essential in making numerical weather prediction feasible.

- Computing the trajectory of a spacecraft requires the accurate numerical solution of a system of ordinary differential equations.

- Car companies can improve the crash safety of their vehicles by using computer simulations of car crashes. Such simulations essentially consist of solving partial differential equations numerically.

- Hedge funds (private investment funds) use tools from all fields of numerical analysis to attempt to calculate the value of stocks and derivatives more precisely than other market participants.

- Airlines use sophisticated optimization algorithms to decide ticket prices, airplane and crew assignments and fuel needs. Historically, such algorithms were developed within the overlapping field of operations research.

- Insurance companies use numerical programs for actuarial analysis.

The rest of this section outlines several important themes of numerical analysis.

History

[lemba | kulemba source]The field of numerical analysis predates the invention of modern computers by many centuries. Linear interpolation was already in use more than 2000 years ago. Many great mathematicians of the past were preoccupied by numerical analysis,[5] as is obvious from the names of important algorithms like Newton's method, Lagrange interpolation polynomial, Gaussian elimination, or Euler's method. The origins of modern numerical analysis are often linked to a 1947 paper by John von Neumann and Herman Goldstine,[6][7][8] but others consider modern numerical analysis to go back to work by E. T. Whittaker in 1912.[6]

To facilitate computations by hand, large books were produced with formulas and tables of data such as interpolation points and function coefficients. Using these tables, often calculated out to 16 decimal places or more for some functions, one could look up values to plug into the formulas given and achieve very good numerical estimates of some functions. The canonical work in the field is the NIST publication edited by Abramowitz and Stegun, a 1000-plus page book of a very large number of commonly used formulas and functions and their values at many points. The function values are no longer very useful when a computer is available, but the large listing of formulas can still be very handy.

The mechanical calculator was also developed as a tool for hand computation. These calculators evolved into electronic computers in the 1940s, and it was then found that these computers were also useful for administrative purposes. But the invention of the computer also influenced the field of numerical analysis,[5] since now longer and more complicated calculations could be done.

The Leslie Fox Prize for Numerical Analysis was initiated in 1985 by the Institute of Mathematics and its Applications.

Direct and iterative methods

[lemba | kulemba source]Consider the problem of solving

- 3x3 + 4 = 28

for the unknown quantity x.

| 3x3 + 4 = 28. | |

| Subtract 4 | 3x3 = 24. |

| Divide by 3 | x3 = 8. |

| Take cube roots | x = 2. |

For the iterative method, apply the bisection method to f(x) = 3x3 − 24. The initial values are a = 0, b = 3, f(a) = −24, f(b) = 57.

| a | b | mid | f(mid) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 3 | 1.5 | −13.875 |

| 1.5 | 3 | 2.25 | 10.17... |

| 1.5 | 2.25 | 1.875 | −4.22... |

| 1.875 | 2.25 | 2.0625 | 2.32... |

From this table it can be concluded that the solution is between 1.875 and 2.0625. The algorithm might return any number in that range with an error less than 0.2.

Discretization and numerical integration

[lemba | kulemba source]

In a two-hour race, the speed of the car is measured at three instants and recorded in the following table.

| Time | 0:20 | 1:00 | 1:40 |

|---|---|---|---|

| km/h | 140 | 150 | 180 |

A discretization would be to say that the speed of the car was constant from 0:00 to 0:40, then from 0:40 to 1:20 and finally from 1:20 to 2:00. For instance, the total distance traveled in the first 40 minutes is approximately (2/3 h × 140 km/h) = 93.3 km. This would allow us to estimate the total distance traveled as 93.3 km + 100 km + 120 km = 313.3 km, which is an example of numerical integration (see below) using a Riemann sum, because displacement is the integral of velocity.

Ill-conditioned problem: Take the function f(x) = 1/(x − 1). Note that f(1.1) = 10 and f(1.001) = 1000: a change in x of less than 0.1 turns into a change in f(x) of nearly 1000. Evaluating f(x) near x = 1 is an ill-conditioned problem.

Well-conditioned problem: By contrast, evaluating the same function f(x) = 1/(x − 1) near x = 10 is a well-conditioned problem. For instance, f(10) = 1/9 ≈ 0.111 and f(11) = 0.1: a modest change in x leads to a modest change in f(x).

Direct methods compute the solution to a problem in a finite number of steps. These methods would give the precise answer if they were performed in infinite precision arithmetic. Examples include Gaussian elimination, the QR factorization method for solving systems of linear equations, and the simplex method of linear programming. In practice, finite precision is used and the result is an approximation of the true solution (assuming stability).

In contrast to direct methods, iterative methods are not expected to terminate in a finite number of steps. Starting from an initial guess, iterative methods form successive approximations that converge to the exact solution only in the limit. A convergence test, often involving the residual, is specified in order to decide when a sufficiently accurate solution has (hopefully) been found. Even using infinite precision arithmetic these methods would not reach the solution within a finite number of steps (in general). Examples include Newton's method, the bisection method, and Jacobi iteration. In computational matrix algebra, iterative methods are generally needed for large problems.[9][10][11][12]

Iterative methods are more common than direct methods in numerical analysis. Some methods are direct in principle but are usually used as though they were not, e.g. GMRES and the conjugate gradient method. For these methods the number of steps needed to obtain the exact solution is so large that an approximation is accepted in the same manner as for an iterative method.

Discretization

[lemba | kulemba source]Furthermore, continuous problems must sometimes be replaced by a discrete problem whose solution is known to approximate that of the continuous problem; this process is called 'discretization'. For example, the solution of a differential equation is a function. This function must be represented by a finite amount of data, for instance by its value at a finite number of points at its domain, even though this domain is a continuum.

Generation and propagation of errors

[lemba | kulemba source]The study of errors forms an important part of numerical analysis. There are several ways in which error can be introduced in the solution of the problem.

Round-off

[lemba | kulemba source]Round-off errors arise because it is impossible to represent all real numbers exactly on a machine with finite memory (which is what all practical digital computers are).

Truncation and discretization error

[lemba | kulemba source]Truncation errors are committed when an iterative method is terminated or a mathematical procedure is approximated and the approximate solution differs from the exact solution. Similarly, discretization induces a discretization error because the solution of the discrete problem does not coincide with the solution of the continuous problem. In the example above to compute the solution of , after ten iterations, the calculated root is roughly 1.99. Therefore, the truncation error is roughly 0.01.

Once an error is generated, it propagates through the calculation. For example, the operation + on a computer is inexact. A calculation of the type is even more inexact.

A truncation error is created when a mathematical procedure is approximated. To integrate a function exactly, an infinite sum of regions must be found, but numerically only a finite sum of regions can be found, and hence the approximation of the exact solution. Similarly, to differentiate a function, the differential element approaches zero, but numerically only a nonzero value of the differential element can be chosen.

Numerical stability and well-posed problems

[lemba | kulemba source]Numerical stability is a notion in numerical analysis. An algorithm is called 'numerically stable' if an error, whatever its cause, does not grow to be much larger during the calculation.[13] This happens if the problem is 'well-conditioned', meaning that the solution changes by only a small amount if the problem data are changed by a small amount.[13] To the contrary, if a problem is 'ill-conditioned', then any small error in the data will grow to be a large error.[13]

Both the original problem and the algorithm used to solve that problem can be 'well-conditioned' or 'ill-conditioned', and any combination is possible.

So an algorithm that solves a well-conditioned problem may be either numerically stable or numerically unstable. An art of numerical analysis is to find a stable algorithm for solving a well-posed mathematical problem. For instance, computing the square root of 2 (which is roughly 1.41421) is a well-posed problem. Many algorithms solve this problem by starting with an initial approximation x0 to , for instance x0 = 1.4, and then computing improved guesses x1, x2, etc. One such method is the famous Babylonian method, which is given by xk+1 = xk/2 + 1/xk. Another method, called 'method X', is given by xk+1 = (xk2 − 2)2 + xk.[note 1] A few iterations of each scheme are calculated in table form below, with initial guesses x0 = 1.4 and x0 = 1.42.

| Babylonian | Babylonian | Method X | Method X |

|---|---|---|---|

| x0 = 1.4 | x0 = 1.42 | x0 = 1.4 | x0 = 1.42 |

| x1 = 1.4142857... | x1 = 1.41422535... | x1 = 1.4016 | x1 = 1.42026896 |

| x2 = 1.414213564... | x2 = 1.41421356242... | x2 = 1.4028614... | x2 = 1.42056... |

| ... | ... | ||

| x1000000 = 1.41421... | x27 = 7280.2284... |

Observe that the Babylonian method converges quickly regardless of the initial guess, whereas Method X converges extremely slowly with initial guess x0 = 1.4 and diverges for initial guess x0 = 1.42. Hence, the Babylonian method is numerically stable, while Method X is numerically unstable.

- Numerical stability is affected by the number of the significant digits the machine keeps. If a machine is used that keeps only the four most significant decimal digits, a good example on loss of significance can be given by the two equivalent functions

- and

- Comparing the results of

- and

- by comparing the two results above, it is clear that loss of significance (caused here by catastrophic cancellation from subtracting approximations to the nearby numbers and , despite the subtraction being computed exactly) has a huge effect on the results, even though both functions are equivalent, as shown below

- The desired value, computed using infinite precision, is 11.174755...

- The example is a modification of one taken from Mathew; Numerical methods using MATLAB, 3rd ed.

Areas of study

[lemba | kulemba source]The field of numerical analysis includes many sub-disciplines. Some of the major ones are:

Computing values of functions

[lemba | kulemba source]|

Interpolation: Observing that the temperature varies from 20 degrees Celsius at 1:00 to 14 degrees at 3:00, a linear interpolation of this data would conclude that it was 17 degrees at 2:00 and 18.5 degrees at 1:30pm. Extrapolation: If the gross domestic product of a country has been growing an average of 5% per year and was 100 billion last year, it might extrapolated that it will be 105 billion this year.  Regression: In linear regression, given n points, a line is computed that passes as close as possible to those n points.  Optimization: Suppose lemonade is sold at a lemonade stand, at $1.00 per glass, that 197 glasses of lemonade can be sold per day, and that for each increase of $0.01, one less glass of lemonade will be sold per day. If $1.485 could be charged, profit would be maximized, but due to the constraint of having to charge a whole-cent amount, charging $1.48 or $1.49 per glass will both yield the maximum income of $220.52 per day.  Differential equation: If 100 fans are set up to blow air from one end of the room to the other and then a feather is dropped into the wind, what happens? The feather will follow the air currents, which may be very complex. One approximation is to measure the speed at which the air is blowing near the feather every second, and advance the simulated feather as if it were moving in a straight line at that same speed for one second, before measuring the wind speed again. This is called the Euler method for solving an ordinary differential equation. |

One of the simplest problems is the evaluation of a function at a given point. The most straightforward approach, of just plugging in the number in the formula is sometimes not very efficient. For polynomials, a better approach is using the Horner scheme, since it reduces the necessary number of multiplications and additions. Generally, it is important to estimate and control round-off errors arising from the use of floating-point arithmetic.

Interpolation, extrapolation, and regression

[lemba | kulemba source]Interpolation solves the following problem: given the value of some unknown function at a number of points, what value does that function have at some other point between the given points?

Extrapolation is very similar to interpolation, except that now the value of the unknown function at a point which is outside the given points must be found.[14]

Regression is also similar, but it takes into account that the data are imprecise. Given some points, and a measurement of the value of some function at these points (with an error), the unknown function can be found. The least squares-method is one way to achieve this.

Solving equations and systems of equations

[lemba | kulemba source]Another fundamental problem is computing the solution of some given equation. Two cases are commonly distinguished, depending on whether the equation is linear or not. For instance, the equation is linear while is not.

Much effort has been put in the development of methods for solving systems of linear equations. Standard direct methods, i.e., methods that use some matrix decomposition are Gaussian elimination, LU decomposition, Cholesky decomposition for symmetric (or hermitian) and positive-definite matrix, and QR decomposition for non-square matrices. Iterative methods such as the Jacobi method, Gauss–Seidel method, successive over-relaxation and conjugate gradient method[15] are usually preferred for large systems. General iterative methods can be developed using a matrix splitting.

Root-finding algorithms are used to solve nonlinear equations (they are so named since a root of a function is an argument for which the function yields zero). If the function is differentiable and the derivative is known, then Newton's method is a popular choice.[16][17] Linearization is another technique for solving nonlinear equations.

Solving eigenvalue or singular value problems

[lemba | kulemba source]Several important problems can be phrased in terms of eigenvalue decompositions or singular value decompositions. For instance, the spectral image compression algorithm[18] is based on the singular value decomposition. The corresponding tool in statistics is called principal component analysis.

Optimization

[lemba | kulemba source]Optimization problems ask for the point at which a given function is maximized (or minimized). Often, the point also has to satisfy some constraints.

The field of optimization is further split in several subfields, depending on the form of the objective function and the constraint. For instance, linear programming deals with the case that both the objective function and the constraints are linear. A famous method in linear programming is the simplex method.

The method of Lagrange multipliers can be used to reduce optimization problems with constraints to unconstrained optimization problems.

Evaluating integrals

[lemba | kulemba source]Numerical integration, in some instances also known as numerical quadrature, asks for the value of a definite integral.[19] Popular methods use one of the Newton–Cotes formulas (like the midpoint rule or Simpson's rule) or Gaussian quadrature.[20] These methods rely on a "divide and conquer" strategy, whereby an integral on a relatively large set is broken down into integrals on smaller sets. In higher dimensions, where these methods become prohibitively expensive in terms of computational effort, one may use Monte Carlo or quasi-Monte Carlo methods (see Monte Carlo integration[21]), or, in modestly large dimensions, the method of sparse grids.

Differential equations

[lemba | kulemba source]Numerical analysis is also concerned with computing (in an approximate way) the solution of differential equations, both ordinary differential equations and partial differential equations.[22]

Partial differential equations are solved by first discretizing the equation, bringing it into a finite-dimensional subspace.[23] This can be done by a finite element method,[24][25][26] a finite difference method,[27] or (particularly in engineering) a finite volume method.[28] The theoretical justification of these methods often involves theorems from functional analysis. This reduces the problem to the solution of an algebraic equation.

Software

[lemba | kulemba source]Since the late twentieth century, most algorithms are implemented in a variety of programming languages. The Netlib repository contains various collections of software routines for numerical problems, mostly in Fortran and C. Commercial products implementing many different numerical algorithms include the IMSL and NAG libraries; a free-software alternative is the GNU Scientific Library.

Over the years the Royal Statistical Society published numerous algorithms in its Applied Statistics (code for these "AS" functions is here); ACM similarly, in its Transactions on Mathematical Software ("TOMS" code is here). The Naval Surface Warfare Center several times published its Library of Mathematics Subroutines (code here).

There are several popular numerical computing applications such as MATLAB,[29][30][31] TK Solver, S-PLUS, and IDL[32] as well as free and open source alternatives such as FreeMat, Scilab,[33][34] GNU Octave (similar to Matlab), and IT++ (a C++ library). There are also programming languages such as R[35] (similar to S-PLUS), Julia,[36] and Python with libraries such as NumPy, SciPy[37][38][39] and SymPy. Performance varies widely: while vector and matrix operations are usually fast, scalar loops may vary in speed by more than an order of magnitude.[40][41]

Many computer algebra systems such as Mathematica also benefit from the availability of arbitrary-precision arithmetic which can provide more accurate results.[42][43][44][45]

Also, any spreadsheet software can be used to solve simple problems relating to numerical analysis. Excel, for example, has hundreds of available functions, including for matrices, which may be used in conjunction with its built in "solver".

See also

[lemba | kulemba source]- Category:Numerical analysts

- Analysis of algorithms

- Computational science

- Computational physics

- Gordon Bell Prize

- Interval arithmetic

- List of numerical analysis topics

- Local linearization method

- Numerical differentiation

- Numerical Recipes

- Probabilistic numerics

- Symbolic-numeric computation

- Validated numerics

Notes

[lemba | kulemba source]- ↑ This is a fixed point iteration for the equation , whose solutions include . The iterates always move to the right since . Hence converges and diverges.

References

[lemba | kulemba source]Citations

[lemba | kulemba source]- ↑ "Photograph, illustration, and description of the root(2) tablet from the Yale Babylonian Collection". Archived from the original on 13 Ogasiti 2012. Retrieved 2 Okutobala 2006.

- ↑ Demmel, J.W. (1997). Applied numerical linear algebra. SIAM. doi:10.1137/1.9781611971446. ISBN 978-1-61197-144-6.

- ↑ Ciarlet, P.G.; Miara, B.; Thomas, J.M. (1989). Introduction to numerical linear algebra and optimization. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521327886. OCLC 877155729.

- ↑ Trefethen, Lloyd; Bau III, David (1997). [[[:Template:GBurl]] Numerical Linear Algebra]. SIAM. ISBN 978-0-89871-361-9.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Brezinski, C.; Wuytack, L. (2012). [[[:Template:GBurl]] Numerical analysis: Historical developments in the 20th century]. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-444-59858-5.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ↑ 6.0 6.1 Watson, G.A. (2010). "The history and development of numerical analysis in Scotland: a personal perspective" (PDF). The Birth of Numerical Analysis. World Scientific. pp. 161–177. ISBN 9789814469456.

- ↑

Bultheel, Adhemar; Cools, Ronald, eds. (2010). [[[:Template:GBurl]] The Birth of Numerical Analysis]. Vol. 10. World Scientific. ISBN 978-981-283-625-0.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ↑ Brezinski & Wuytack 2001, p. 2

- ↑ Saad, Y. (2003). [[[:Template:GBurl]] Iterative methods for sparse linear systems]. SIAM. ISBN 978-0-89871-534-7.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ↑ Hageman, L.A.; Young, D.M. (2012). [[[:Template:GBurl]] Applied iterative methods] (2nd ed.). Courier Corporation. ISBN 978-0-8284-0312-2.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ↑ Traub, J.F. (1982). [[[:Template:GBurl]] Iterative methods for the solution of equations] (2nd ed.). American Mathematical Society. ISBN 978-0-8284-0312-2.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ↑ Greenbaum, A. (1997). [[[:Template:GBurl]] Iterative methods for solving linear systems]. SIAM. ISBN 978-0-89871-396-1.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Higham 2002

- ↑ Brezinski, C.; Zaglia, M.R. (2013). [[[:Template:GBurl]] Extrapolation methods: theory and practice]. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-08-050622-7.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ↑ Hestenes, Magnus R.; Stiefel, Eduard (Disembala 1952). "Methods of Conjugate Gradients for Solving Linear Systems" (PDF). Journal of Research of the National Bureau of Standards. 49 (6): 409–. doi:10.6028/jres.049.044.

- ↑ Ezquerro Fernández, J.A.; Hernández Verón, M.Á. (2017). [[[:Template:GBurl]] Newton's method: An updated approach of Kantorovich's theory]. Birkhäuser. ISBN 978-3-319-55976-6.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ↑ Deuflhard, Peter (2006). [[[:Template:GBurl]] Newton Methods for Nonlinear Problems. Affine Invariance and Adaptive Algorithms]. Computational Mathematics. Vol. 35 (2nd ed.). Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-21099-3.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ↑ Ogden, C.J.; Huff, T. (1997). "The Singular Value Decomposition and Its Applications in Image Compression" (PDF). Math 45. College of the Redwoods. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 Sekutembala 2006.

- ↑ Davis, P.J.; Rabinowitz, P. (2007). [[[:Template:GBurl]] Methods of numerical integration]. Courier Corporation. ISBN 978-0-486-45339-2.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ↑ Weisstein, Eric W. "Gaussian Quadrature". MathWorld.

- ↑ Geweke, John (1996). "15. Monte carlo simulation and numerical integration". Handbook of Computational Economics. Vol. 1. Elsevier. pp. 731–800. doi:10.1016/S1574-0021(96)01017-9. ISBN 9780444898579.

- ↑ Iserles, A. (2009). [[[:Template:GBurl]] A first course in the numerical analysis of differential equations] (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-73490-5.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ↑ Ames, W.F. (2014). [[[:Template:GBurl]] Numerical methods for partial differential equations] (3rd ed.). Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-08-057130-0.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ↑ Johnson, C. (2012). [[[:Template:GBurl]] Numerical solution of partial differential equations by the finite element method]. Courier Corporation. ISBN 978-0-486-46900-3.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ↑ Brenner, S.; Scott, R. (2013). [[[:Template:GBurl]] The mathematical theory of finite element methods] (2nd ed.). Springer. ISBN 978-1-4757-3658-8.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ↑ Strang, G.; Fix, G.J. (2018) [1973]. An analysis of the finite element method (2nd ed.). Wellesley-Cambridge Press. ISBN 9780980232783. OCLC 1145780513.

- ↑ Strikwerda, J.C. (2004). [[[:Template:GBurl]] Finite difference schemes and partial differential equations] (2nd ed.). SIAM. ISBN 978-0-89871-793-8.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ↑ LeVeque, Randall (2002). [[[:Template:GBurl]] Finite Volume Methods for Hyperbolic Problems]. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-43418-8.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ↑ Quarteroni, A.; Saleri, F.; Gervasio, P. (2014). [[[:Template:GBurl]] Scientific computing with MATLAB and Octave] (4th ed.). Springer. ISBN 978-3-642-45367-0.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ↑ Gander, W.; Hrebicek, J., eds. (2011). [[[:Template:GBurl]] Solving problems in scientific computing using Maple and Matlab®]. Springer. ISBN 978-3-642-18873-2.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ↑ Barnes, B.; Fulford, G.R. (2011). Mathematical modelling with case studies: a differential equations approach using Maple and MATLAB (2nd ed.). CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4200-8350-7. OCLC 1058138488.

- ↑ Gumley, L.E. (2001). [[[:Template:GBurl]] Practical IDL programming]. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-08-051444-4.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ↑ Bunks, C.; Chancelier, J.P.; Delebecque, F.; Goursat, M.; Nikoukhah, R.; Steer, S. (2012). Engineering and scientific computing with Scilab. Springer. ISBN 978-1-4612-7204-5.

- ↑ Thanki, R.M.; Kothari, A.M. (2019). [[[:Template:GBurl]] Digital image processing using SCILAB]. Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-89533-8.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ↑ Ihaka, R.; Gentleman, R. (1996). "R: a language for data analysis and graphics" (PDF). Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics. 5 (3): 299–314. doi:10.1080/10618600.1996.10474713.

- ↑ Bezanson, Jeff; Edelman, Alan; Karpinski, Stefan; Shah, Viral B. (1 Janyuwale 2017). "Julia: A Fresh Approach to Numerical Computing". SIAM Review. 59 (1): 65–98. doi:10.1137/141000671. hdl:1721.1/110125. ISSN 0036-1445. S2CID 13026838.

- ↑ Jones, E., Oliphant, T., & Peterson, P. (2001). SciPy: Open source scientific tools for Python.

- ↑ Bressert, E. (2012). SciPy and NumPy: an overview for developers. O'Reilly. ISBN 9781306810395.

- ↑ Blanco-Silva, F.J. (2013). Learning SciPy for numerical and scientific computing. Packt. ISBN 9781782161639.

- ↑ Speed comparison of various number crunching packages Archived 5 Okutobala 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Comparison of mathematical programs for data analysis Archived 18 Meyi 2016 at the Portuguese Web Archive Stefan Steinhaus, ScientificWeb.com

- ↑ Maeder, R.E. (1997). Programming in mathematica (3rd ed.). Addison-Wesley. ISBN 9780201854497. OCLC 1311056676.

- ↑ Wolfram, Stephen (1999). [[[:Template:GBurl]] The MATHEMATICA® book, version 4]. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781579550042.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ↑ Shaw, W.T.; Tigg, J. (1993). Applied Mathematica: getting started, getting it done (PDF). Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0-201-54217-2. OCLC 28149048.

- ↑ Marasco, A.; Romano, A. (2001). [[[:Template:GBurl]] Scientific Computing with Mathematica: Mathematical Problems for Ordinary Differential Equations]. Springer. ISBN 978-0-8176-4205-1.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help)

Sources

[lemba | kulemba source]- Golub, Gene H.; Charles F. Van Loan (1986). Matrix Computations (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-5413-X.

- Higham, Nicholas J. (2002) [1996]. Accuracy and Stability of Numerical Algorithms. Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics. ISBN 0-89871-355-2.

- Hildebrand, F. B. (1974). Introduction to Numerical Analysis (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-028761-9.

- Leader, Jeffery J. (2004). Numerical Analysis and Scientific Computation. Addison Wesley. ISBN 0-201-73499-0.

- Wilkinson, J.H. (1988) [1965]. The Algebraic Eigenvalue Problem. Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-853418-1.

- Kahan, W. (1972). A survey of error-analysis. Proc. IFIP Congress 71 in Ljubljana. Info. Processing 71. Vol. 2. North-Holland. pp. 1214–39. ISBN 978-0-7204-2063-0. OCLC 25116949. (examples of the importance of accurate arithmetic).

- Trefethen, Lloyd N. (2008). "IV.21 Numerical analysis" (PDF). In Leader, I.; Gowers, T.; Barrow-Green, J. (eds.). [[[:Template:GBurl]] Princeton Companion of Mathematics]. Princeton University Press. pp. 604–614. ISBN 978-0-691-11880-2.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help)

External links

[lemba | kulemba source]Journals

[lemba | kulemba source]- Numerische Mathematik, volumes 1–..., Springer, 1959–

- volumes 1–66, 1959–1994 (searchable; pages are images). (in English and German)

- Journal on Numerical Analysis (SINUM), volumes 1–..., SIAM, 1964–

Online texts

[lemba | kulemba source]- Template:Springer

- Numerical Recipes, William H. Press (free, downloadable previous editions)

- First Steps in Numerical Analysis (archived), R.J.Hosking, S.Joe, D.C.Joyce, and J.C.Turner

- CSEP (Computational Science Education Project), U.S. Department of Energy (archived 2017-08-01)

- Numerical Methods, ch 3. in the Digital Library of Mathematical Functions

- Numerical Interpolation, Differentiation and Integration, ch 25. in the Handbook of Mathematical Functions (Abramowitz and Stegun)

Online course material

[lemba | kulemba source]- Numerical Methods (Archived 28 Julayi 2009 at the Wayback Machine), Stuart Dalziel University of Cambridge

- Lectures on Numerical Analysis, Dennis Deturck and Herbert S. Wilf University of Pennsylvania

- Numerical methods, John D. Fenton University of Karlsruhe

- Numerical Methods for Physicists, Anthony O’Hare Oxford University

- Lectures in Numerical Analysis (archived), R. Radok Mahidol University

- Introduction to Numerical Analysis for Engineering, Henrik Schmidt Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Numerical Analysis for Engineering, D. W. Harder University of Waterloo

- Introduction to Numerical Analysis, Doron Levy University of Maryland

- Numerical Analysis - Numerical Methods (archived), John H. Mathews California State University Fullerton

Template:Areas of mathematics Template:Branches of physics Template:Computer science

- CS1 errors: URL

- Harv and Sfn no-target errors

- Webarchive template wayback links

- Webarchive template other archives

- Articles with short description

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Use dmy dates from October 2020

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Pages using Sister project links with hidden wikidata

- Articles with English-language sources (en)

- Articles with German-language sources (de)

- Articles with BNF identifiers

- Articles with BNFdata identifiers

- Articles with GND identifiers

- Articles with J9U identifiers

- Articles with LCCN identifiers

- Articles with NKC identifiers

- Numerical analysis

- Mathematical physics

- Computational science